For every child, clean air at home

UNICEF works with government partners to protect rural children from indoor air pollution

- Available in:

- 中文

- English

What do you know about air pollution? Most people would picture a smoggy skyline, dark fumes rising from chimneys, or the exhaust pipes of idling cars - something in the open air. However, air pollution in the home is often overlooked, even though it could cause as much or greater harm, especially to children, compared to outdoor pollution.

According to a survey1 released by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (formerly the Ministry of Environmental Protection) in 2016, around 32 per cent of children in rural areas of China are exposed to indoor air pollution caused by cooking or heating with solid fuels, such as firewood and coal. Studies have shown that air pollution is detrimental to the health, growth and development of fetuses and infants. It may cause premature birth, low birth weight, asthma, respiratory tract infections, cancer, and affect brain development.

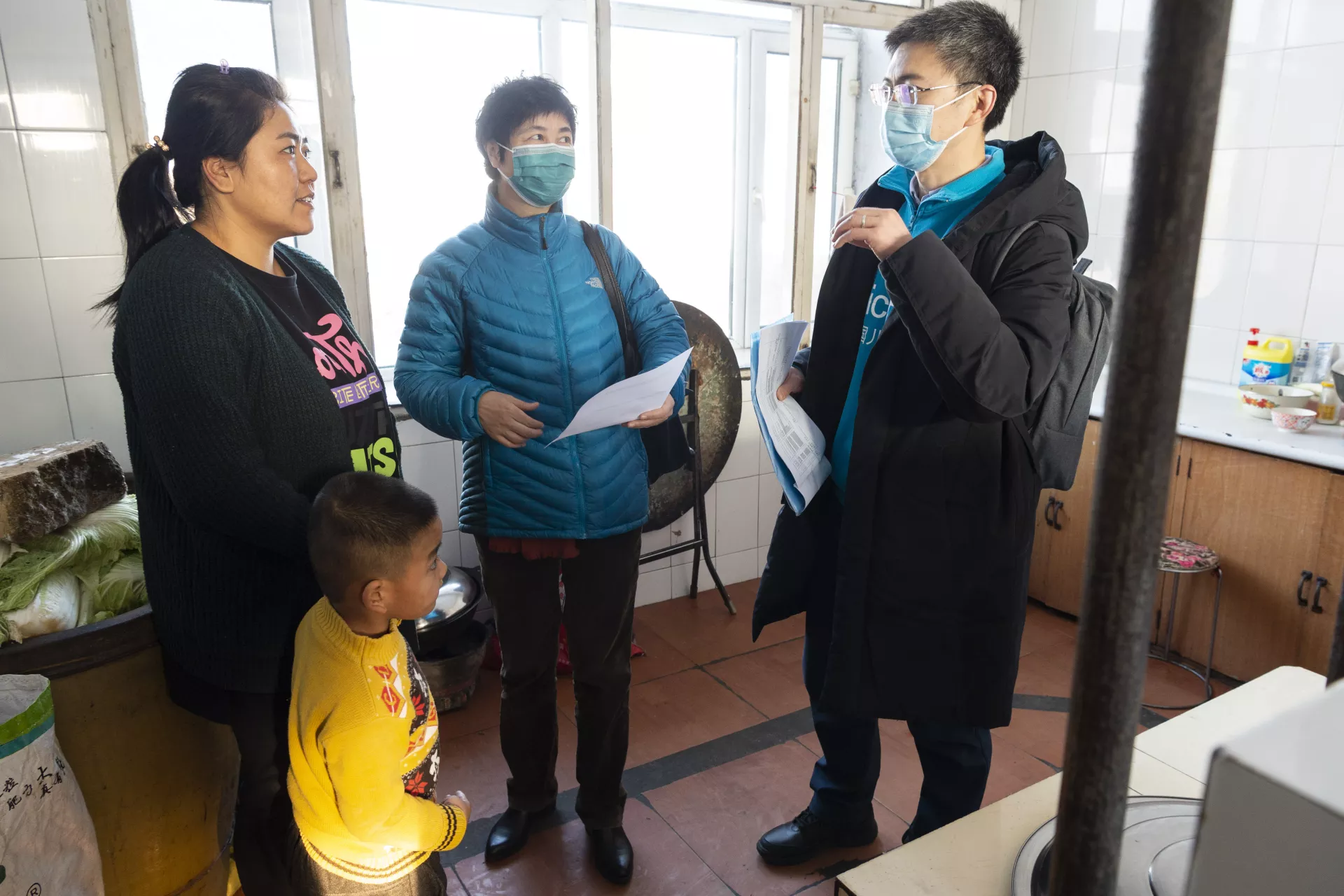

Since December 2019, UNICEF has partnered with China’s National Health Commission and the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention to implement a pilot programme to reduce the impact of indoor air pollution on children's health in Jiamusi in Heilongjiang Province and Mianyang in Sichuan Province. The project explores strategies such as air quality monitoring and introducing air purifiers, chimney ventilation, and fans. These are integrated with health communication to raise parents’ awareness of environmental health so that they can reduce indoor air pollution and protect their children.

1 Environmental Exposure-Related Activity Patterns Survey of the Chinese Population (Children)

In Huachuan County of Jiamusi, temperatures in winter can drop to minus 30° C. Residents indicated that they usually use coal-burning stoves at least two or three times a day to stay warm. This exposes them and their children to prolonged indoor air pollution, which is a significant health risk. During the pilot programme, we found that indoor PM2.5 concentration in many rural homes reached or exceeded 999 μg/m3 – the highest reading possible on the air quality monitor – during cooking and heating. Most of the interviewed families saw this as normal. The World Health Organization recommends the 24-hour average level of PM2.5 should not exceed 25 μg/m3.

UNICEF is developing strategies and advocating for policies that will replace coal-burning cooking and heating sources with clean-energy appliances. We are also advising parents to keep children away from sources of pollution and ensure better ventilation while using coal-burning stoves. The project is also exploring the impacts of introducing chimney ventilation, fans and air purifiers on reducing exposure to pollutants. In addition, we installed real-time indoor air quality monitors to remind villagers to take timely actions when the air quality’s reading exceeds a certain level.

We saw that many households have access to a natural gas supply and induction cookers. However, community members are often unaware of the serious impacts of indoor pollution on health. For the sake of saving costs and the difficulty of breaking away from traditional tastes and ways of cooking, wood stoves are still widely used, exposing them and their children to indoor air pollution.

For example, rural families often make smoked meat. During a visit to the project site in Anzhou District of Mianyang, we saw a mother cooking for her children in the kitchen. The mother was cooking over firewood, with smoked meat hanging from the ceiling. Her children were sitting close by, not only inhaling harmful smoke, but also at risk of burns. Moving away from traditional preferences for cooking is difficult and requires sustained health education, replacement of appliances, and incentives to change behaviour.

Increasing community members’ awareness of the health risks of indoor pollution is a priority of the project. At first we conducted face-to-face communication, but during the COVID-19 pandemic, we mainly conducted health education online. An increasing number of families are now better informed about the impact of indoor pollution on children’s health. Families are trying their best to keep their children away from air pollution sources, and many people have dropped the habit of using plastic products to ignite fires.

We will continue to guide families to reduce indoor air pollution through health communication. We will also evaluate the effects of this pilot project, review experiences from the initiative, and inform national efforts to formulate and implement intervention strategies for children's indoor air pollution, so that every child can grow up healthily in a clean air environment.