It's never too remote or too cold for a Barefoot Social Worker

It's never too remote or too cold for a Barefoot Social Worker

- Available in:

- 中文

- English

For the six-year-old looking eagerly out her grandparents' window, the village social worker could not walk fast enough. When at last the door opens, the tiny Uyghur girl jumps into the arms of the barefoot social worker, repeatedly mumbling “sister, sister” and hugging her tightly.

The young girl's mother died three days after she was born. At five months, Halisha was diagnosed with congenital heart disease. Soon after, her father left the family home and has never returned. Halisha lives with her farming grandparents, whose annual income from the little wheat and corn they can grow, is insufficient to afford the medical treatment Halisha requires.

The little girl is not the only one in desperate need of help in rural China. For the vast population of young people left behind with grandparents or on their own by one or both parents who have disappeared or moved to cities to find employment or for children in impoverished households, the barefoot social workers are as part of an experimental project to develop a national frontline model for child welfare response.

Officially termed Child Welfare Directors, the barefoot social workers in the project provide a desperately needed and welcomed role in some of China's most impoverished counties: they are spreading comfort. Equally critical, they are connecting impoverished children with available government schemes that help to alleviate some of the family burdens.

Trained in basic child psychological skills and a full understanding of all government social assistance schemes, the non-professional ‘social workers' at this point largely serve to help the Government reach children entitled to the available benefits.Although they are not certified social work professionals, their training on China's social assistance schemes and their regular home visits help the Government reach children entitled to available benefits.

For instance, because enrolment in the hukou system is required to access China's social assistance schemes, the village barefoot social workers check that all children are registered and help those who are not to register.

And though the village barefoot social workers are not trained or authorized to look for potential cases of abuse or neglect, through their home visits they may learn of problems or can provide parenting information that discourages harsh punishment.

Supported by the Ministry of Civil Affairs and UNICEF, the Barefoot Social Worker project is operating in 120 villages in five provincial-level regions including Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, where these three stories were collected, following two barefoot social workers' home visits.

Helping children access life-saving medical treatment

Rukeyan met Halisha in 2011 during her first round of home visits as the barefoot social worker of Hotan Maili Village. She reported the situation to the local civil affairs authority and enrolled Halisha into a medical aid programme of the Ministry of Civil Affairs. Within months, Halisha was sent to a hospital in the regional capital, Urumqi, for a heart operation. The government programme covered the medical expenses and half of the travel expenses.

While she was in hospital, Halisha's doctors discovered she also suffered from hydrocephalus, which is excess fluid in the brain that can be damaging (headaches, nausea, blurred vision or problems in walking or talking) that requires a small plastic device to help the fluid drain. Due to the family's financial difficulties, the grandparents took her home without the treatment because they could not afford it.

As it turned out, Halisha's condition did affect her speech development. In 2014, Rukeyan again arranged for free treatment at a hospital in Yining City to relieve the fluid. But the damage remains. Halisha can only speak words that have no more than two syllables, but she cannot complete a sentence. She communicates with the help of gestures and facial expressions.

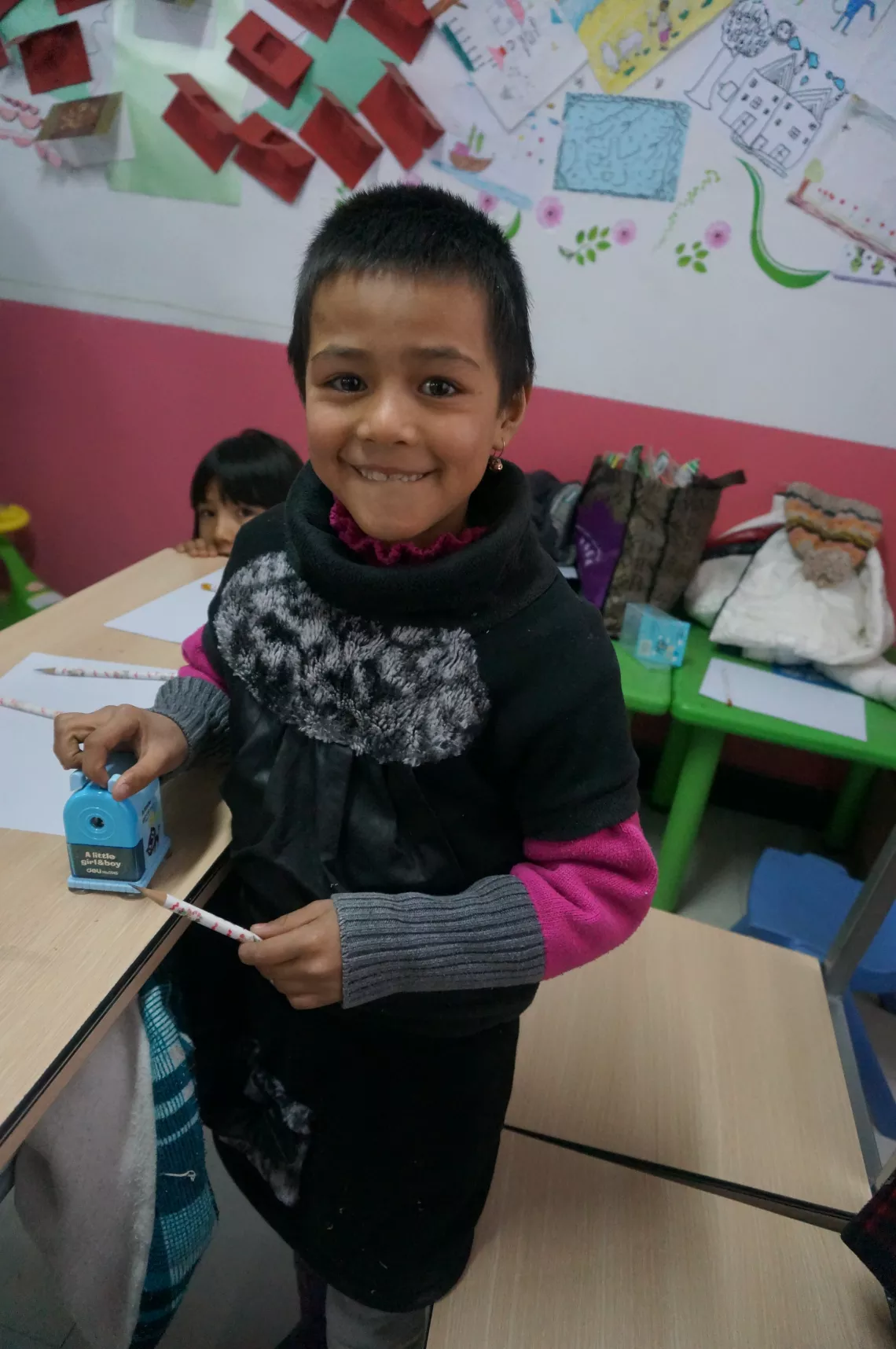

Halisha attends kindergarten nowadays but because of her language difficulties, her grandparents have decided to have her repeat kindergarten rather than go to first grade in September so she can strengthen her speech.

Rukeyan often visits Halisha, bringing snacks and clothes. They play games and take photos of themselves with Rukeyan's telephone. Before the start of kindergarten, Rukeyan bought Halisha a schoolbag, notebooks, pencils and crayons. Halisha shows off the schoolbag to a visitor, repeating the word “mine”.

Rukeyan's visits have given Halisha confidence around strangers and she greets strangers with almost the same open glee she showers on the village barefoot social worker. But her grandparents are consumed with worries for her well-being when they are gone.

“What will happen to her if one day soon we pass away?” The grandmother asks, choking back tears while holding Halisha in her arms. Halisha, whose eyes are bright and fringed with long lashes, stares curiously at her grieving grandmother.

“I'm 67. I don't know for how long I can look after her,” says her grandfather.

Helping children with disabilities

Dongdong, 22, and his brother Feifei, 17, both have cerebral palsy and difficulties with their speech and movement. The younger son could not walk on his own until last year.

“He wasn't even able to put on his shoes by himself. I kept helping him to do that until recently,” says his mother, Chen Hongxia. She stopped enrolling him in school after the second grade.

With limited income their father earned helping others in their village with farming or construction needs, the two sons received no special health care as they grew. At least, not until their village was selected for inclusion in the Barefoot Social Worker project.

In December 2013, the barefoot social worker, Fan Juying, introduced Feifei to the government programme for rehabilitation therapy for people with disabilities.

Two months later, Feifei travelled to Beijing from his home in the far western Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region for a surgical procedure provided free of charge through government assistance. Three months later he could walk unassisted. “And I can put on shoes all by myself,” he says slowly but proudly.

Although the older brother's condition is similar to Feifei's but less severe, the government assistance is available only to children younger than 17. By the time the family learned about the program, Dongdong was ineligible.

Eager to talk, Dongdong says he stayed in school through the fifth grade. “Now I stay at home and sometimes help raise the chicken and pigs.”

“I like to go to the children's space, where I learn to read,” Dongdong adds, noting he is reading a textbook of his brother's.

The children's space is part of the Barefoot Social Worker project. Located in the building of village committee, it provides a play area for village children. It ordinarily opens at the weekend, and opens daily when school is out for summer and winter breaks. The Child Welfare Director of the village always organizes some activities at the children's space, such as lectures, book club and sport games.

Fan says the brothers come often to play table tennis; she sees them walking hand in hand to and from the space.

Dongdong continues talking about his yearnings for the kind of life other men his age enjoy and hopes one day to have a job. “I know how to sweep away the snow, clean the floor and wash the dishes,” he explains.

His mother is not so optimistic on employment prospects for either son. “It's not possible, and they are never going to recover. My husband and I will look after them as long as we can, but what then?”

Helping families in poverty

Near dusk on a farm in rural Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, two young boys crunched through a thick layer of snow and the below-freezing temperature to a shabby shed where their cattle waited to be fed. With his bare hands stinging from the cold, the 12-year-old boy pushed an ox towards the trough.

After their father was sentenced to five years in prison for theft and their mother became unable to carry on farming because of tuberculosis, the elder boy, now 16, dropped out of school to tend to the corn and the cattle – the family's only source of income.

They invested in the cattle last year, through a bank loan, to supplement the meagre earnings from their corn harvest. Nearly all their income for the past year was used to pay back the loan. “There is not even a penny left,” says the boys' mother, Mayinu.

Fan Juying, the barefoot social worker, often visits the family to check on their needs. Sometimes she brings them rice or flour.

The family house in this ethnic Kazak community is tiny, and visitors could hardly turn around in the living room, which becomes the dining room at mealtime and the bedroom at night. Another room is packed with buckets and bags of fertilizer and feed.

Fan says Ye'erlan, the elder boy, performed exceptionally well academically and she tried to convince him to stay in school. The family's extreme poverty left him no choice, he had told her. With Fan's help, Ye'erlan attended a vocational school for one year and then found a waiter job in a hotel in the city, 38 kilometres from his home.

But he had to quit after four months when his mother's illness worsened. Ye'erlan returned to care for her. It was then the family borrowed from the bank to invest in cattle. Ye'erlan sometimes goes to the city for part-time work when there is no farm income.

Asked whether he will resume his studies, Ye'erlan quivers to hold back his tears but shakes his head. “I'm too old to go back to school, and I just want a stable job to support my younger brother. All I hope is that he works hard at school. Now that I'm out of school, there is no way that I will let him do the same,” he says.

“Barefoot Social Workers address the last mile challenge of policy implementation. Based in the community and close to the children, they can promptly identify children and families who are in desperate help and provide them the much needed support. For vulnerable families, the long distance to county seats, where service providers are located, and the relatively complex process in application and approval make the services especially inaccessible. A Barefoot Social Worker, with first-hand knowledge of children's needs, the government policies and the required procedure to meet these needs, fills the gap,” said Xu Wenqing, a UNICEF Programme Specialist.

“The active engagement of the Barefoot Social Worker has served to identify the once invisible child welfare and protection issues. By spotting and reporting these issues to relevant government departments, the most disadvantaged children can access their entitled social assistance and protection.”